CLASSIFICATION

Swallow ID:

6274

Partner Institution:

Simon Fraser University

Source Collection Title:

Reading in BC Collection

Source Collection ID:

MsC 199

Source Collection Description:

Reading in BC collection was assembled during the late 1970s and ‘80s. There are approximately 1000 tapes in this collection. It consists of the recordings of Canadian and American writers, mostly poets, reading poems, talking, being interviewed, participating in panel discussions, and so on. Most of the recordings were made in BC, but there are some made elsewhere in Canada or the USA. Quite a few of these recordings are unique copies, not to be found elsewhere.

Source Collection Contributing Unit:

SFU Library

ITEM DESCRIPTION

Title:

Sacred Geography Seminar with Prof. Robin Blaser on October 29, 1976 tape 2 of 2 #634

Title Source:

j-card

Title Note:

Liner notes: see the photo in the material description

Language:

English

Production Context:

Documentary recording

Identifiers:

[RB_634]

Rights

Rights:

In Copyright (InC)

CREATORS

Name:

Blaser, Robin

Dates:

1925-2009

Role:

Speaker

MATERIAL DESCRIPTION

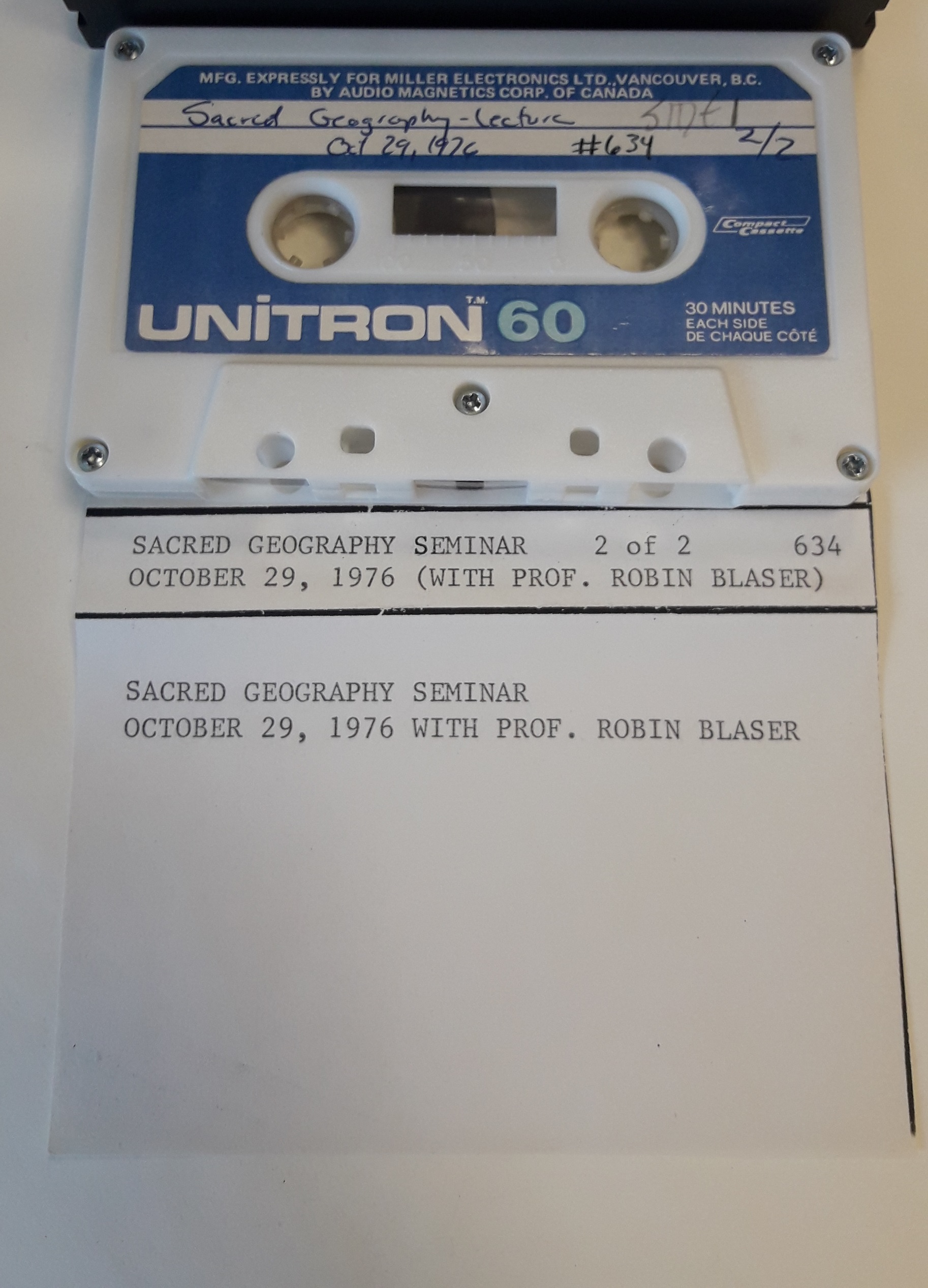

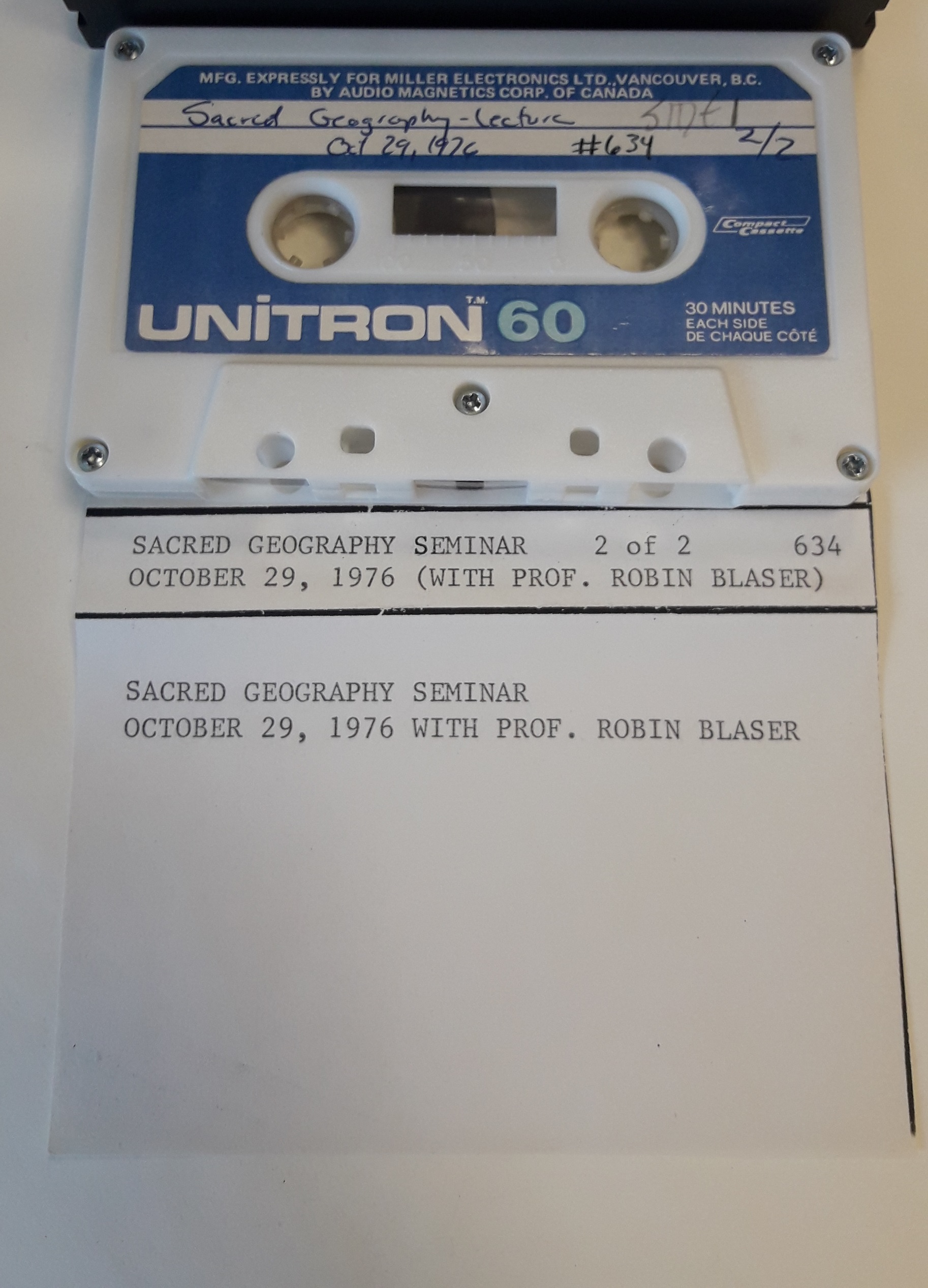

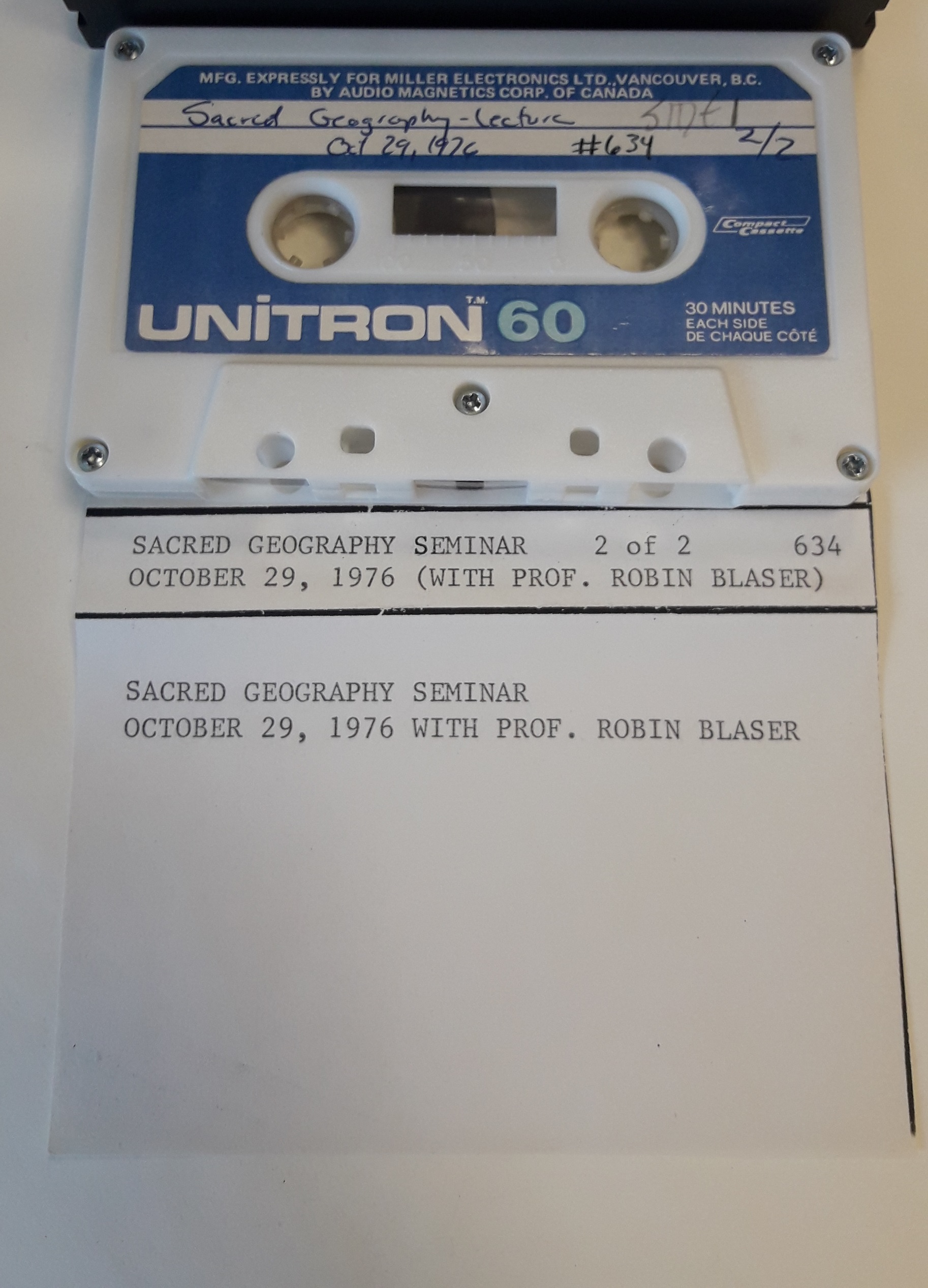

Image:

Recording Type:

Analogue

AV Type:

Audio

Material Designation:

Cassette

Physical Composition:

Magnetic Tape

Extent:

1/8 inch

Sound Quality:

Excellent

Physical Condition:

Excellent

Other Physical Description:

Clear box with j-card

DIGITAL FILE DESCRIPTION

Channel Field:

Stereo

Sample Rate:

44.1 kHz

Duration:

T00:30:31

Size:

29.3 MB

Bitrate:

32 bit

Encoding:

WAV for master files and .MP3 for online files

Content Type:

Sound Recording

Channel Field:

Stereo

Sample Rate:

44.1 kHz

Duration:

T00:34:05

Size:

33.3 MB

Bitrate:

32 bit

Encoding:

WAV for master files and .MP3 for online files

Content Type:

Sound Recording

Dates

Date:

1976-10-29

Type:

Performance Date

Source:

J-card

LOCATION

Address:

8888 University Dr, Burnaby, BC, Canada

Venue:

SFU

Latitude:

49.276709600000004

Longitude:

-122.91780296438841

Notes:

Location taken from cassette #631

CONTENT

Contents:

Side Track No. Comments

One 000

002 Tape begins with Blaser’s voice in mid-sentence. References to Olson & nature of the “primary” soon follow

018 The historical task of the poet, the greater context. Once this has been understood one can truly appreciate texts that stand outside their mere contemporary context, the “otherness” of a poetic text

040 The 20th century “consciousness of language”, Blaser agrees that the Romantics started the move towards the notion of language but he thinks it was individuals such as Pound who began to comprehend and appreciate the polar relationships of poetry with a consciousness of the nature of language

074 By way of an investigation into divine poetic nature, Blaser examines texts that detail the relationship between the Ancient (Homeric?) Greeks and their gods

104 The balance of heaven and earth (“earth and sky”) and the emerging notion of “the universe”. “A destiny of the Greeks is neither a justification nor disruption or elimination of the natural course of the world. It is this natural course of the world itself”

130 To create an understanding of the foundation of this world view, Blaser explains that to the Homeric Greeks the world was not an observable, examinable place but a “realm” of “the ever unobjective to which we are subordinate as long as the paths of birth and death, of blessing and curse, hold us thrust into being where the essential lessons of our history befall us and which are taken over and abandoned, misunderstood and again sought by us. Their world’s the world. Prof. Blaser is drawing most of his material from Victor Vycinas’ The Earth and Gods : an introduction to the Philosophy of Martin Heidegger

142 Art as the stabilizer of the lucidity of the world

Prof. Blaser, as he does on other tapes in the series, argues that, as part of human being’s nature, Truth is to be found only in “unreason”. Truth as emerging from the primeval strife to “that which is”. The strife between the world and the earth can “only become Truth when it takes a stand within the realm of openness obtained by it. “….such a “stand” can only be actualized as an Artwork”

220 Hermes, who “what he is, as an example of a deity. The various roles and responsibilities of the god are listed and detailed; an attempt is made by Blaser to limit the god’s many titles into a conceptual whole

269 The discussion on the many traits of Hermes continues

276 Blaser turns onto Zeus “The worldness of a world is Zeus”. Zeus as a god of light, which innately infers that Zeus is a god of revealing, “of disclosing… by reflecting the truth of the god, these forms are true. They are the logos of this god. Zeus, then, is the logos par excellence

289 The nature of Truth. “Truth as Reason, becomes in the poetic argument simply our Reason. And this confronts what Olson calls the “demonic nature of experience”. The link is made easily between this notion and the notion of the polarity, the “tension” of experience in mythology. Reference is made to Charles Olson’s Poetry and Truth (The Beloit Lectures and Poems). In the existence that lies behind poetry, more than the language we speak

311 Return of topic to the “tension of existence”. Blaser notes the interdependence to the “other”. Olson’s so-called attack on Einstein in Poetry and Truth is brought up to display the content of the concept; Einstein’s relativity is viewed as another one of the modes of reason. Olson harkens to the dynamically-relational. A Maurice Merleon-Ponty essay to be found in Sense-non-Sense, is cited by Blaser as summing up the issue at immediate hand here

333 The disclosure of the world the way it appears to the I. Again Olson’s Poetry and Truth is mentioned. One point of particular noteworthiness is that the “I” is to be found “among” not isolated in any manner. Notion of disclosure and concealment; the “active” agent of the unknown

348 Speech as a stance of language, revealing the relationship(s) between intellect and objects. Language and freedom. Freedom as possessing the individual (not vice versa), Spicer and Olson cited. Human referring as a result of the outward mode, Logos, in this primary sense, “is our assembling of otherness to ourselves”

368 Classroom confusion results in Blaser repeating his previous statements to clarify their meaning

384 Martin Heidegger is cited once again, a quotation “Our thinking is giving thanks”. Further quotations are given and explored, all searching for the language behind language

398 Olson’s notion that “so say” (speech) is “to bring into appearance”. Such a notion should not be confused with the “creation” of appearance; words do not follow things”. Olson calls this “Mythologos”, words bringing things from their position of concealment

407 Side One ends

Two 000

003 Blaser’s voice emerges in mid-sentence, discussing such topics as “truth” and “freedom”. The movement toward “the future” and its being is discussed. Vyainds’ is quoted and references to Olson and Spicer are made

029 The future “as “improvised… in Utopias”; with the absence of a tradition, human beings “therefore… constantly break the ties of tradition by revolts”. While the concept seemingly contradicts itself, Blaser proves the opposite to in fact be the case

052 Contemporary human beings standing between philosophy and the upcoming of a greater thought, the thought of being itself”. Blaser, utilizing Heidegger directly, states that thinking of the future assembles the language/being of the future thinking as no longer philosophy but now mythology

106 Operative and Representational language: Representational language represent the “red” of the world. Operative language presents – discloses – what was previously covered. The language is interactive when its operative sense

132 Structural elements of the world: Earth, Sky, Mortals and Gods. Together they make up the “action of the world… its light”. Concealment and Revealment are explored once again; Earth as having a “tendency to concealment, the World to revealment. Art, the Truth, emerges from the strife between the Earth and the World

160 Chaos as “the holiness itself: (L. Heidegger), it stands as the ultimate course of all. The Realm of Destiny, binding everything. Blaser embellishes this fully, conjuring up Heroditas, Spicer and Olson

198 The song of the poet being the place where ghouls, human beings and holiness can all appear. “All true poetry has its beginning in an encounter with the divine”

215 Discussion moves onto earth-centered religions; the cathonoing society in which the dead are real and powerful in that they go to the earth. Blaser notes that Spiker refused to separate the dead and the living, and in fact gave the dead a prominence over the living

229 Olympian religion gains prominence over the Cathonain religion, death is shunned. Numerous references made to Homer’s place in this

247 The reversal of Logos, the reversal of light. Characteristics of Olympian and Cathonain religion are explored in contrast

280 Earth, Sky, Gods, Mortal men – “all of them are in strife, as parts of the world”. Art as a creating a world, creating a hold on the “earth in the world”. The guarding of the earth and the world in their strife is a fundamental feature of Art work. Letting the Truth take place in the struggle between the worldness of the world and earth

311 Blaser draws a transition connecting concepts of the ancient world with the contemporary interest in “open form”. Charles Olson is cited as using such “open form” as projective and as field; Jack Spicer is also cited for his “serial poems’ a constant opening of time itself

322 Blaser vocalizes his view that he feels the “openform” vs. “closed form” debate is little more than an intellectual “hang-up”

330 The nature of “open form”; openness as it is “attached to a primary condition” – the narrative as a new stance, a new content. Blaser quotes

340 Closing remarks. Blaser answers a class question. Blaser reading (his own work?)

359 Side Two ends

Notes:

SFU BC Readings formatting

NOTES

Note:

Part 1 of 2 is on tape #635